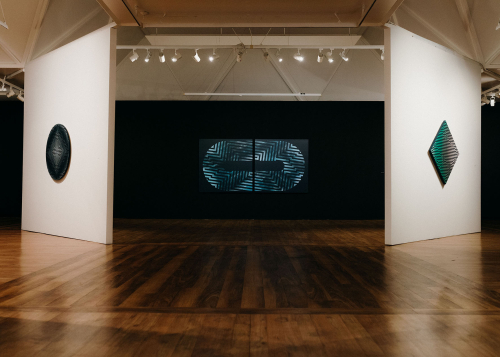

Hemi Macgregor's Waiora at Te Whare Toi o Heretaunga Hastings Art Gallery. Works include Maramataka (2022) (on left), Moana nui a Kiwa (centre), Tai Pari (2022) (on right). Photo/Putaanga Waitoa

The journey from darkness and the illumination that knowledge brings recognises Tāne-te-waiora, the atua of life, light and wellbeing. Waiora, named after this atua, is a solo exhibition by Hemi Macgregor (Ngāti Rākaipaaka, Ngāti Kahungunu, Ngāi Tūhoe) that was shown at Hastings Art Gallery from 17 December 2022 to 16 April 2023. This exhibition aligns te hauora o te tāngata, the wellbeing of people, with te hauora o te ao, the wellbeing of the world. To be in good relation with a place, and to understand ourselves as part of the whenua, can be restorative for Māori, and grounding for Pākehā. Waiora (also translated as the life-giving water) flows so that life can blossom.

Hemi Macgregor’s art practice draws on pūrākau that link te taiao, the environment, to the roles and rules of engagement we as tāngata have within it. Painting, sculpture and installation are brought forth to create geometric structures and patterns. In exploring line and form, and creating dynamic layers and textures, his artworks embody a bold visual language of colour and light. This language gives voice to his whakapapa, and the generations of carvers, artists and storytellers before him who have contributed to his understanding of wellbeing, vitality and health.

Alongside stencil work, spray paint is a key medium for Macgregor. ‘Toirehu’ is te reo Māori for spray paint, and the etymology of rehu (meaning spray or mist) is spoken over his paintings, seen as the viewer moves in close and notices the sparseness of colour misted onto the surface. Its mist-like substance and quality are akin to the different states of water.

In speaking with me about the artworks in Waiora, Macgregor connects a love of art and his exploration of the world around him with his whakapapa and to the whare whakairo, Te Poho o Te Rehu, in Nūhaka. Macgregor recalls waiting for the sun to rise from behind the hills, feeling the moisture that lingers in the air just before the sun hits the earth: the browns and oranges of the dry grass sharing the same sightline with the blue morning sky. When the sun rises at Nūhaka, you only have a few hours before the misty morning dissipates into the scorching day.

The colours in his work reflect the colours of his memories of home – the painting Rehutai (2022), for example, is orange and brilliant blue, reminiscent of a new day and clear sky in Nūhaka. On a square plywood panel painted with a black ground, the orange and blue converge in mists of spray paint. The colours, evenly coating the surface on the left and right respectively, are more dispersed as they reach the centre, disappearing as they meet there and overlap. From a distance, the tone appears grey; up close it reveals the dance of the two colour-mists being drawn from the air onto the surface of the plywood. Patterning negative space across the painting are stencilled geometric outlines, like those in kete whakairo, that lead up, down, and off the edges.

Hukatai (2022) hangs with Rehutai (2022), on the walls that greet you as you enter the gallery, like the amo at the front of the whare. The paintings share the same square form and painted stencil reliefs, but the colours of Hukatai are colder in tone. The crossing of colours from pink to crimson red to turquoise is like the effect of Rayleigh scattering in the sky at sunrise and sunset.

Rehutai and Hukatai are also the names of the stones of knowledge collected with the baskets of knowledge by Tāne-te-waiora. These names can be associated with a canoe en passage on the sea. Hukatai, the white stone, is the wake of the ocean’s surface generated by a canoe in motion, traversing at dawn, symbolising the pursuit of knowledge in centring oneself and regulating a direction in life. Rehutai, the red stone, is the bow of a canoe whipping up seafoam, the sun’s rays piercing the foam creating a rainbow effect. This is waiora – illumination. Waiora is an exhibition where everyone can learn about care, stewardship and aroha by taking the time to be with these artworks that carry the names of atua.

Our relationship with te taiao is seen in everyday moments of life. Macgregor shares with me memories he has of mornings at his wharenui, Te Poho o Te Rehu, and fishing at Māhia; he tells me about these places and the commonalities they share with his life today. He relates this to the metaphysical truth of looking forward and backward and saying, “I am in this moment”, as all of his tīpuna have been in this moment. Aunties and uncles have sat on the chairs on the porch of the wharekai Katea, drinking cups of tea, waiting for the day of mahi to begin.

Sharing a story of a recent fishing trip, Macgregor talks about a guy he noticed throwing his fishing net into the water, while others were surf casting. This was a revelation to Macgregor, seeing a place so alive with people in a relationship with the ngutu-awa, gathering kai. The river has a life to it – the life of humans and the life of the beings within the river. Wellbeing manifests in the responsibilities we as people have – in paying attention to them today, we ensure a healthy tomorrow. When do we put out nets? When do we not? What fish are there to eat in each different breeding season? All of these questions convey the confluence of activity at a river mouth.

Ngutu-awa, Ngutu-ika, Ngutu-tangata (2022) is a diptych of square plywood hung vertically. Its pattern shifts to a monochromatic mist of white dispersed over a black ground. This paintwork embosses a structural combination of relief lines formed in the likenesses of poutama, rau kūmara and pātiki. This work reflects the life of the river mouth in warmer months when the schools of smaller fish swim near the surface. Ngutu-awa, the lips of the river, is a beautiful term that allows us to personify atua in a less abstract way. The paired paintings purse together, reflecting and rippling as lips themselves. We don’t need to be abstract and separate when we can know and experience the world we are a part of.

Macgregor started looking at pūrākau and practices around gathering kai. These are embedded in the ngahere, māra kai, takutai, shallow waters and deeper oceans. Macgregor explores the importance of locating oneself in a place and having ongoing responsibilities to the natural cycles, shifts and occurrences embedded within one’s environment. Atua are these places, and in naming his paintings after atua, Macgregor invites viewers of his works to think about the relationships they have with the areas they visit and reside in; the energies in those areas that are atua.

Each name recalls more than the linear significance of a signpost or label – it carries within itself expansive knowledges. The name of each artwork reveals threads Macgregor has followed as an act of rangatiratanga – the strength of leadership that understands a broader view of weaving multiple threads together.

There are rongoā that resonate with the relationship between atua and tāngata. Our pūrākau link us back to locations and activities, like fishing, and connect us physically with atua and their domains, instead of leading us towards personification and idolatry of atua as abstracted deities, far removed. Ngutu-awa, Ngutu-ika, Ngutu-tangata is an example of this. Awa, ika and tāngata are responsible to and acknowledge each other – we eat and take only what is necessary, in order for the others to remain healthy.

Tai Timu (2022) and Tai Pari (2022) are paintings that reference the incoming and outgoing tides. Tai Timu is a circular plywood work with Macgregor’s characteristic black ground and geometric stencilling. From the left side, a warm, red spray-paint is misted fainter and fainter, leaving the right side enveloped by the dark. Tai Pari is a diamond-shaped plywood with the same black ground, with seafoam-green spray-paint misted from the left, fainter at the centre as it is met by a burst of white spray-paint fading out from right to left. The colours are like a rolling wave crashing at the shore. The names of these artworks also appear in waiata sung at tangi, guiding times of despair and referencing the natural flow of life and death.

Moving out from the river mouth, Hine Moana (2022) and Parawhenuamea (2022) are works depicting Kiwa’s two wives and how they exist with each other. These two sculptural tōtara works, circular in form, are routed with contours that pattern and echo in a similar way to his paintings. These routed concave lines, zigzagging and outlining square and rhomboid shapes, play with the gallery lighting, letting angles of shadow and light hit the works’ curves and peaked edges. Hine Moana is the ocean who mothers and cares for shellfish, eels, seaweed and octopus, and Parawhenuamea is fresh and alluvial waters. Between them, the two atua care for the different kinds of fish and plants that live respectively within each. Our atua that embody the largest bodies of water are the names of the works that flank the side walls of the exhibition. Wainui ātea (2022), the vast and mighty ocean, is a large horizontal oval shape, made of tōtara, hanging on the left-hand wall. It has large routed contours that echo out around a hollowed centre marked with angled contours of a smaller scale that repeatedly meet, ascending and descending. Moana nui a Kiwa (2022) is in clear view from the front entrance of the exhibition space, and is comprised of two squares of plywood painted with a black ground, hanging in a horizontal diptych. Together the squares connect a portal that Macgregor has painted with crossing mists of white and blue spray-paint. The stencil forms create a sense of tilt, evoking the view one has on board a boat in the swaying ocean.

Maramataka (2022) shows multiple overlays of diamonds formed from misted white against black. The structural geometric lines translate as the perimeter of a white diamond at the centre echoes out in a fainter spray... Maramataka references the moon and its phases, and the low and high energies of the moon: the way water levels in soil affect plant growth; indicating the times to be industrious and times to be still.

Whetumarama (2022) has layered misted diamond shapes that allow the centre to recede and disappear into the black background. The work speaks of the bright stars in the sky, appearing and signalling seasons of the year, while the orchestral installation Te Pōtangotango (2022) envisions Te Ika-whenua-o-te-rangi, the Milky Way, as an array of clustered whauwhaupaku flowers blossoming in winter.

Pātikitiki (2022) and Rua Pātiki (2022) use similar techniques of stencilling and spray paint. These are the names of the nebulous cloud near Mahutonga, the Southern Cross constellation, named in connection to the holes dug by flounder in the riverbed and the murky clouds left behind as they swim away. The expanse and darkness of the night sky embrace the viewer. The rhomboid forms that appear in these paintings are reminiscent of the artist’s mother’s raranga. In Toitū Te Whenua, Toitū Te Moana, Toitū Te Tangata at Mahara Gallery, Waikanae (2021), Macgregor presented a kete similarly depicting a woven form of his father’s Macgregor tartan.

Waiora builds on Macgregor’s previous presentation of work – both at Mahara Gallery and in the group exhibition Matarau at City Gallery Wellington (2022). His artworks open a space to kōrero about lived and remembered experiences that draw our attention to our place in the world. Macgregor paints and sculpts with clarity in a space of creativity, reciprocity and responsibility. Approaching what he feels, sees and believes, he has created an expression of what has revealed itself to him. Macgregor’s artworks are a language of recovery and vitality, concerned with discovering an inheritance worth preserving.

Waiora by Hemi Macgregor was shown at Te Whare Toi o Heretaunga - Hastings Art Gallery, 17 December 2022 – 16 April 2023. This essay was originally published by Pantograph Punch.

Disclaimers and Copyright

While every endeavour has been taken by the Hastings City Art Gallery to ensure that the information on this website is

accurate and up to date, Hastings City Art Gallery shall not be liable for any loss suffered through the use, directly or indirectly, of information on this website. Information contained has been assembled in good faith.

Some of the information available in this site is from the New Zealand Public domain and supplied by relevant

government agencies. Hastings City Art Gallery cannot accept any liability for its accuracy or content.

Portions of the information and material on this site, including data, pages, documents, online

graphics and images are protected by copyright, unless specifically notified to the contrary. Externally sourced

information or material is copyright to the respective provider.

© Hastings City Art Gallery - www.hastingscityartgallery.co.nz / +64 6 8715095 / hastingsartgallery@hdc.govt.nz